Depictions of Japan in Giacomo Puccini’s Madama Butterfly (1904) and Somtow Sucharitkul’s Dan-no-Ura (2014)

A final year undergraduate dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Music, University of Cambridge

By Mickey Wongsathapornpat

Abstract

These two operas, created over a century apart in very different cultural contexts, are both set in Japan, one in its composer’s time (early 1900s) and the other in the distant Heian period (in 1185). The country portrayed in them is, therefore, vastly different. However, a common thread can be found in many aspects of Japanese culture seen in the two works, from religion to traditional music. By comparing the treatment of these topics in two operas conceived in such contrasting circumstances, we can begin to appreciate the significance of Japan as a theme in both works. In this study, I aim to find new ways of looking at these operas through the lens of Japanese culture and to examine the validity of opinions on the topic in the current literature. By exploring and comparing these works against their historical and social backdrops, their composers’ source materials (musical or otherwise) and the understanding of Japan they shared with their audiences, this study hopes to add to the discussion of these operas and to help inform possible future performances.

Introduction

Somtow Sucharitkul (b.1952) is a Thai-American composer and author. Having studied at Cambridge and lived in Japan and the USA as a science-fiction writer, he is acquainted with both Western and non-Western musical and literary traditions. His opera Dan-no-Ura (2014), premiered in Bangkok, is inspired by the account of the eponymous naval battle in the fourteenth-century Japanese epic Heike Monogatari (The Tale of Heike). He wrote the libretto in English, largely adapting it from Chapter 11 of the epic, preserving many of the original passages as well as adapting scenes from other parts of the epic to create coherent character arcs.

With a Wagnerian-sized orchestra, Dan-no-Ura is one of very few full-scale operas set in Japan by a non-Japanese composer after Puccini; like Madama Butterfly (1904), it uses Japanese musical idioms and a common-practice-derived tonality. The aim here is to illustrate any common ground, to discern any differences and to provide an interpretation based on their respective circumstances and source materials. This study will also consider the successes and shortcomings in portraying Japanese cultural reality, and the extent to which it reflects cultural or social change between the Heian period (twelfth century) and the Meiji period in which Dan-no-Ura and Butterfly are respectively set. By looking at these works through facets of Japanese culture, I wish to show that – despite Sucharitkul having a better cultural grounding than Puccini – Butterfly is more culturally accurate than has previously been suggested.

Puccini’s critics often took sides either to whitewash or to emphasise those elements of sexism and Orientalism that he shares with his contemporaries. While not denying its partial influence, in light of Sucharitkul’s work and his modern-day vision of Japan, we should reconsider the retrospective value-judgements that have been directed at Butterfly. A comparison with a culturally sensitive opera such as Dan-no-Ura enables us to reappraise Butterfly. This study also aims to discuss evidence surfaced since the 1990s concerning the origins of musical materials used by Puccini. On the other hand, it will be the first to analyse the work of Sucharitkul; as such, it hopes to contribute to the neglected field of modern musicology in Thailand.

Religion and aesthetic values are the most pervasive facets of Japanese culture in both operas. In Chapter 1, I argue that examining both operas through this lens can provide a deeper meaning to the characterisation, as well as to the way each work is structured.

Chapter 2 looks more broadly into the questions about portraying groups of people: class, race, gender and political factions. Here, I aim to show that different groups of people can be delineated with Japanese cultural values, such as ‘death before dishonour’, and that Butterfly can be read with a non-racist/sexist connotation when compared with Dan-no-Ura.

Chapter 3 looks at the influence of Japanese music itself in the musical language of each opera. I argue that – despite using Japanese sources differently – both portray Japanese culture with music effectively through motivic development and different strategies in placing Japanese music in the score.

1. Religion and Aesthetics

Introduction

This chapter argues that in order to understand Japan as found in each opera, it must first be examined through the theme of religion and aesthetics, both of which are inextricably linked in Japanese culture. First, I aim to establish that compared to Dan-no-Ura, Puccini’s portrayal of religion in Japan is less flawed than previously claimed due to its syncretic nature. Then I look at the Buddhist teaching on impermanence, which is an influential theme in Dan-no-Ura, and propose that its presence can also be seen in Butterfly. Finally, I examine the influence of various Japanese aesthetic ideals, some of which are influenced by the concept of impermanence itself, on the underlying structure of each work.

1.1 Religious syncretism

Religion in itself is a highly influential theme in both operas. For example, an important moment in Madama Butterfly – when the protagonist is disowned by her family – is caused by her conversion to Christianity. Ever since Buddhism was introduced in Japan from the Asian continent during the sixth century, its relationship with the native Shintoism shows a high level of practical syncretism, a fusion officially called Shinbutsu-shūgō.[1] This means, for instance, that an individual can worship both the native deities (kami) and the Buddha, and disregard any theological contradiction between either belief systems. This mindset is important for understanding the portrayal of the seemingly confused religious practice found in both works.

Much has been written to criticise the inaccuracies found in the representation of religion in Butterfly – tracing them as far back as its sources, J. L. Long’s short story and David Belasco’s play. Arthur Groos, for example, discussed in detail how Butterfly’s prayer at the beginning of the play (equivalent to Suzuki’s prayer at the beginning of Butterfly’s Act 2) jumbled the invocation of “Shaka” (Shakyamuni, or the Buddha) with references to personal cleanliness and hand clapping, which he correctly identified as a Shinto practice. Groos does not mention other, similar cases: in Puccini’s version, Butterfly’s Buddhist Bonze uncle is seen to invoke the Shinto deity Sarutahiko (corrupted here as “Sarundasico”) at I:105[2]. These inaccuracies may be distracting, at least to the modern Japanese audience, as evident in Tokyo’s NPO Opera’s “cleanup” of these details in a 2004 production.[3] Groos’s criticism is understandable, too, coming from a globalised twentieth-century standpoint that retrospectively denounces the fin-de-siècle Orientalist tendencies as ignorant and superficial. While such errors could have arisen from limited or inaccurate information, an attempt to systematically distinguish the practice between these two religions as suggested by Groos would be excessive, as it ignores the existence of religious syncretism in Japan. It is not unheard of at all for an individual, for instance, to be cleansed before praying to Buddha, or to revere Buddha in a Shinto-like household shrine (aButsudan) as described in the play.

Therefore, the confusions perceived in Butterfly’s libretto by Groos originate both in the variety of its fictional or quasi-fictional literary sources (Loti, Long and Belasco),[4] and in the reality of Japanese culture, in which the original author (Loti) had presumably observed the blending of the two belief systems in day-to-day practice. Nonetheless, it can be observed that Puccini and his librettists put more effort into researching and representing the reality of Japan than their sources: Groos noted the increased attention to detail in the Japanese aspects in the libretto. In this regard, the attempt that resulted in the jumbled name “Sarundasico” is perhaps a more commendable effort than, say, naming a character “Kyoto” as per Mascagni’s Iris (1898).

Similarly, Dan-no-Ura clearly demonstrates the Japanese Buddhist-Shinto syncretism during the flourishing of Buddhism in the Heian period, the same kind portrayed in Butterfly. For instance, in Part 14 of the opera, before the drowning of the child Emperor Antoku, his grandmother Nii Dono, in her final monologue, instructs him to:

Turn to the East

to the great [Shinto] Shrine of Ise,

and bid it farewell.

[…] turn to the West [India]

and murmur the name

of Amida Buddha.

Here, the theological functions of the two religions are clearly distinguished, but viewed as equals. This represents the religious attitudes of the Heian imperial family: by a traditional Shinto belief, the Emperor claims descent from the Shinto Sun Goddess Amaterasu,[5] whose dedicated place of worship is the Imperial Shrine of Ise. By parting with the Shrine in death, Antoku rhetorically signifies an end to his emperorship, the legitimacy of which derives from the relationship with Amaterasu. Meanwhile, the function of Buddhism here is seen on a more personal, salvific level. Antoku’s prayer to the Amitābha (“Amida” in Japanese) represents the core Buddhist belief in saṃsāra, the cycle of rebirth, to which all humans are subject. As this is a passage not found in the original epic, Nii Dono’s allusion shows Sucharitkul’s understanding of the syncretic religious nature during this period.

The peak in the Heian period of Buddhist influence on the Japanese aristocracy, who historically worshipped Shinto deities (prior to Asuka period, sixth century), would influence the mixed religious practices of the population in later ages as demonstrated in Butterfly during the Meiji period. In fact, the Meiji period is interesting in itself, as the government took the never-before-seen step of separating the two belief systems for the first time in suppressing Buddhism.[6] Its effect on day-to-day people, especially the models on which Butterfly was based, demands further study.

1.2 Buddhism and impermanence

Of the many mixed Buddhist-Shinto beliefs, the core Buddhist teaching on life’s impermanence is arguably the most influential in Japanese culture, being the central theme of Dan-no-Ura. Although this is not immediately apparent in Butterfly, it nevertheless influences the trajectory of the protagonist’s tragedy. Thus, impermanence should first be considered in the context of its manifestation in Dan-no-Ura.

In this opera, the message of impermanence is seen on three levels: in the wabi-sabi aesthetic,[7] in character development, and in the music. A general aristocratic fashion during the Heian era was to constantly contemplate things transient (such as life and happiness) with a deep, gentle sadness.[8] This is reflected in contemporary literature such as the Heike Monogatari, portraying the ephemeral power of the Heike. Much of this melancholic pathos in the original source has been preserved in the libretto. For example, the renowned opening passage, which laments the impermanence of all things,[9] is lifted into the libretto to form the text of the identical Parts 1 (Prelude) and 15 (Postlude). The text is sung by an omniscient chorus, acting as a thematic emblem at the beginning and ending, emphasising the opera’s central message.

The life of Butterfly as portrayed by Puccini can also be seen as an example of impermanence. As Greenwald noted, Puccini’s decision to set the opera in a single setting helps the audience track the protagonist’s life-cycle from marriage to death.[10] Greenwald does not emphasise, however, how much this Buddhist concept of impermanence actually resonates in Puccini’s version, especially when compared to his sources. For instance, the Act 1 libretto shows Butterfly’s initial entrance to her wedding saying “Io sono la fanciulla più lieta del Giappone” (I:39). This emotion is seen completely reversed towards the end, when Butterfly realises that Pinkerton is leaving with her son: “Ah! Triste madre! Abbandonar mio figlio!” (III:38). The imagery of Butterfly’s transient happiness as a girl, which becomes anguish as a mother due to Pinkerton’s abandonment stands in parallel with the Heike’s short-lived power owing to their defeat to the Genji. It also stands in stark relief relative to Belasco’s version due to the added marriage scene that emphasised Butterfly’s happiness prior to subsequent events.

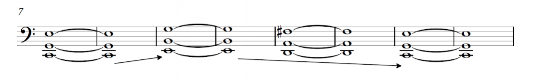

The motto motif of Dan-no-Ura, the most pervasive musical element in the whole opera, also portrays impermanence by symbolising the concept itself (Fig. 1). The ascending third and stepwise descent symbolises the human attempt at acquiring worldly attributes – happiness, riches, beauty etc. – then losing them through transience, according to Buddhist doctrine. This alludes to the Heike’s temporary height as the imperial clan that is later lost to the Genji. Sucharitkul develops this motif extensively in a Wagnerian manner: it is found throughout the score in various keys and orchestrations either as a foreboding device or as an orchestral “comment” on any mention or action relating to the theme of impermanence.

Fig. 1 - The “impermanence” motif, Part 1, Dan-no-Ura

In Butterfly, what Groos terms the “pseudo-ume-no-haru” motif (see 3.2 - Fig. 12) is generally associated with Butterfly’s father or with the foreshadowing of death, functioning as an orchestral “comment” in a similar way to the above “impermanence” motif of Dan-no-Ura. Alternatively, this motif can be taken to signify Butterfly’s impermanence as resulting from her karma. (The Buddhist spiritual principle of karma constitutes the belief that individual actions influence one's future.) For instance, Groos interestingly noted the “pseudo-ume-no-haru” eruption at the end of “Io seguo il mio destino” (I:81), which he sees as predicting Butterfly’s fleeting life as a Japanese woman who failed to assume a Western identity. What he did not realise about the placement of the “pseudo-ume-no-haru” motif (which he initially hypothesised as representing her fear of getting caught by her relatives for renouncing her traditional religion) is that he has been referring to the later 1906 version, and that the motif makes more semantic sense in the context of the opera’s original 1904 version. Here, Butterfly ridicules her old religion by discarding dolls of her ancestors saying “E questi via!”,[11] signifying her departure from her previous values. While Budden opined that the moment is only a “savage outburst” of the motif, What can be drawn from both Groos’s and Budden’s readings is that its placement here could also represent the notion of Butterfly’s karma. The cascade of events leading to her death, through her family’s and Pinkerton’s abandonment, can be given an alternative interpretation – by which Butterfly’s impermanence is her karma for abandoning her traditional religious ways. The idea is given a greater weight with the “pseudo-ume-no-haru” motif’s menacing presence towards the end, at the point at which she pulls out the dagger belonging to her father, the most “ideologically Japanese” figure in the opera,[12] which can be taken to represent the return of the traditional values to her character in death.

Impermanence is further typified in Dan-no-Ura’s character development. Here, the realisation of life’s impermanence is used to humanise the otherwise ruthless Genji characters, Yoshitsune and Kumagae, as reflected by their ambivalence towards war. In a scene in Sucharitkul’s libretto not found in the original epic, for instance, Kumagae’s Part 9 soliloquy reflects on his killing of Emperor Antoku’s flute-playing cousin Atsumori, lamenting the ease with which death befalls man:

I killed a boy.

Why did the gods create such beauty

when a single blow can crush it?

[…]

As I strike him [Atsumori] down, I weep.

Kumagae’s melancholic “aware” revelation appears to be a turning point for his character arc, which in the epic took place before the events of the opera, causing his worldview to be imparted with Buddhist dharma (teaching) and melancholic resignation.

This aware realisation is later shown to contagiously affect Yoshitsune’s character, who is hitherto portrayed as a one-dimensional, ruthless warlord. In Yoshitsune's soliloquy in Part 13, he weeps upon reflecting on his role in the imminent defeat of the Heike:

If you, O Kumagae,

wept tears of salt,

when you killed the beautiful flute player

[…] should I not weep

tears of blood

knowing that I must kill

a little child

who asked not to be Emperor?

Here, his regret towards Atsumori's death can be considered to embody how life’s transience can affect the sensibility of even the most brutal of characters in Dan-no-Ura. As the subject matter of Kumagae’s soliloquy, Atsumori initiates another prevalent musical motif played by two offstage piccolos (Fig. 2) first presented at the dramatic climax of the soliloquy, complete with Atsumori’s own onstage apparition. The motif, comprising a bitonal figure imitated a tritone apart, can be taken to represent the transition of souls between the earthly and spiritual realms (a Shinto idea) with the tritone representing their separated planes being juxtaposed to each other. The motif is given a heightened rhetorical significance later on as when combined with the “impermanence” motif in Part 9’s ending, together signifying the Buddhist teaching on the inevitability of death (i.e. transition of souls in Shinto terms). This thematic innovation, not seen in the original source, further emphasises the relationship between Buddhist and Shinto values in the opera.

Fig. 2 - The “spiritual realm” motif, Part 9, Dan-no-Ura.

1.3 Structure of the opera

The influence of impermanence on Japanese aesthetics can be seen in the ideal of wabi-sabi[13], which teaches to embrace transience, by celebrating wear-and-tear and asymmetry over perfection and geometrical ideals. This, along with other ideals, seems to influence the dramatic construction of both operas. Although it cannot be proven to have directly influenced either composer's thought processes, understanding the deeper-level construction through these concepts helps one understand how the resulting dramatic pacing achieved effectiveness.

For instance, the Jo-ha-kyū ideal that governs the structure of traditional Japanese plays (Nō and Kabuki), calls for action to begin slowly, then accelerate, then end swiftly in order to leave a thrilling, lasting audience impression. The dramatic pacing across Butterfly agrees with this principle whereby Act 3, the shortest amongst all three acts, concentrates on Butterfly’s anguish upon discovering her abandonment, leading to the climactic suicide. Groos observed that Puccini’s construction of the build-up of Butterfly’s death in Act 3 was inspired by Sadayakko’s Kabuki performance in Milan, which impressed him in its “efficacy” in the race towards the ending[14] which was emulated in his own dramatic pacing of Butterfly. We can then postulate that Puccini was indirectly influenced by Jo-ha-kyū. Note that this three-act structure is by no means unique in Western drama: in his preceding opera, Tosca, Act 3 also leads up to the two protagonists’ deaths. However, the main difference between both acts lies in the fact that in Tosca, the dramatic intensity only builds up after the end of Cavaradossi’s aria “E lucevan le stelle” after long passages of “undramatic”[15] shepherd boy’s song and bells spanning half of the act. Meanwhile in Butterfly, the gravity of her situation is immediately apparent from Pinkerton and Sharpless' entrance near the act's beginning, and is amplified towards the very end, which is more aligned with the Jo-ha-kyū principle of simple acceleration towards a climax.

On the other hand, Jo-ha-kyū does not explain Dan-no-Ura well. Its dramatic structure, being based on the pacing of the Heike Monogatari, does not lend itself to the same principle because the build-up towards the point where the Heike commits mass suicide is originally constructed as a much more linear, organic unfolding of events. In fact, Somtow conceived of the opera as one long tableau with fifteen parts, where development is evenly interspersed.[16] As with Butterfly, Dan-no-Ura is set in one single action-space centred around the Shimonoseki Strait. However, the scenes constantly alternate between the Heike ships, Genji ships and the seaside Imperial Palace, allowing the audience to “zoom in” to different locations in real time, as evident from a fluid, moving camera approach to scene changes. This was especially noted in a review as a “single, sweeping symphonic construction, seamless and completely integrated”,[17] echoing a similar single-set aesthetic in Butterfly as discussed in 1.2.

The genesis of both works involved a decision, at some point, to remove a spatially or temporally detached act from the overall structure. In light of the above, we can comprehend the dramatic advantage that results. For instance, Sucharitkul demonstrated wabi-sabi in the structuring of Dan-no-Ura. The published libretto reveals a dramatically inert epilogue that had not been set to music, taking place in an isolated time frame many years after the climax, at the same Imperial Palace in the Prologue (Scene 2 to 4) whereby the surviving characters reflect on the tragedy of Dan-no-Ura and impermanence in life, being the core message in the opera. This scene (*) would have lent perfect symmetry to the whole structure (Fig. 3), but its dramatic and temporal isolation from the main narrative of the work would greatly dilute the climactic impact of the suicide scene towards the end of Part 14 onto the audience, possibly leading to its omission. By removing the Epilogue, Sucharitkul achieves a simpler overall narrative. Furthermore, it can be seen as a result of upholding the core wabi-sabi value as seen here in the asymmetry created in final new structure.

In parallel to Sucharitkul, Puccini’s decision to remove the Consulate Act in Butterfly not only lessens the theme of East-West conflict that would arise from juxtaposing Butterfly’s home against the American Consulate, as Groos argues,[18] but also achieves a more streamlined and compact dramatic structure overall by removing the one spatially detached portion that would otherwise disturb the single-set ideal: a continuous Jo-ha-kyū construction allowing a sharper focus on the exploration of the relationship between the protagonist’s life-cycle and her own home, which supports Greenwald’s reading.[19]

Fig. 3 - Hypothetical symmetrical construction of Dan-no-Ura.

2. Society and Cultural issues

Introduction

This chapter explores the ways in which each opera delineates groups of people. First, I argue that the theme of impermanence can be extended to an association with death before dishonour, an important theme in both works, to distinguish characters. Then I argue that, when compared with Dan-no-Ura’s libretto, the social divide in Butterfly is not as stark as often proposed. Lastly, I look at the portrayal of the Japanese, aiming to show that a comparison with Dan-no-Ura as well as other operas supports the reading that Butterfly is not inherently sexist or racist.

2.1 Death before dishonour

The morality of suicide in the face of imminent defeat and dishonour is a running theme throughout both operas. In both, the climax corresponds to the participation of the protagonists in a ritual suicide exalting their defiance and heroism. For instance, Butterfly commits suicide after discovering Pinkerton’s abandonment and the loss of her child, having already been disowned by her own family. Meanwhile in Dan-no-Ura, the Heike drown themselves with the Emperor to prevent being taken captive by the Genji. Both composers capitalised on this by using music and text to foreshadow these deaths, so as to build a logical anticipation of this outcome. The musical motifs associated with death, such as the “pseudo-ume-no-haru” motif from Butterfly, are also associated with honour by virtue of being associated with her father’s own honourable death. In Dan-no-Ura, the “impermanence” motif also implies the imminent death of the Heike due to its association with the Chorus Prelude[20].

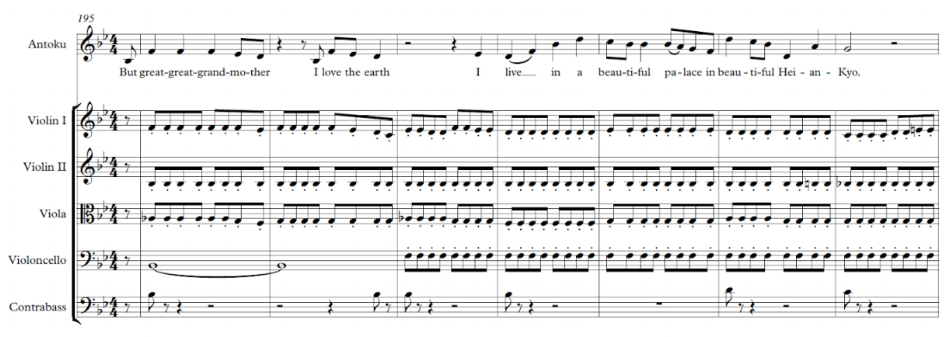

As an overarching theme by itself, death before dishonour is not explicitly present in Heike Monogatari’s Chapter 11 on which Dan-no-Ura is based, but instead Sucharitkul deliberately links it to impermanence and to fate. In the libretto, the Heike’s demise is portrayed as being dictated by the divine deity through a scene not found in the original Heike Monogatari. In Part 11, the Sun Goddess Amaterasu (the same “Ten-sho-dai” of Suzuki) visits Antoku to explain the fate that she had planned for him. Antoku asks her whether he would die, against the foreboding “shadow realm” motif, to which she replies:

Soon you will fulfill

your self-determined destiny.

This exchange, in effect, gives Antoku’s plight a divine legitimacy not originally present in the epic. Later on in Part 14, Nii Dono’s final monologue before the suicide is superimposed on the “impermanence” motif, which is given symbolic meaning here as this is the only time in which the motif ends on a perfect cadence onto scale-degree 1, as shown in (Fig. 4), rather than its “normative” manifestation on scale-degree 3 (Fig. 2). It could then be taken to imply that their prophesied deaths have been fulfilled, restoring her honour.

Fig. 4 - “Impermanence” motif, Part 14, Dan-no-Ura

While the death/dishonour theme is pervasive in Puccini’s sources, in Butterfly, his librettists partially obscured its connection with that of fate. Butterfly’s death echoes the actions of her samurai father. It is inferred in Long’s version that the emperor ordered him to commit suicide to save face for fighting at war on a losing side. This detail was removed in the Act 1 libretto of Puccini’s version, with Goro merely commenting on the emperor’s “invitation”, suicide being implied here by the “pseudo-ume-no-haru” motif. This may have been due to limitations of the libretto medium. Nonetheless, had that detail been left in, it would have strengthened the connection between Butterfly and her father’s deaths, given the symbolism of the “pseudo-ume-no-haru” motif and the use of a dagger, and with her loss of means, family and Pinkerton paralleling her father’s defeat. The implication of this parallel with her father, the most “ideologically Japanese” figure, would also serve to highlight Butterfly failure to abandon her former Japanese identity.

Similarly, in Dan-no-Ura, dishonour is loosely associated with war, but here it is given a more fatalistic connotation. Tomomori, in Part 8, gave a morale-raising speech towards his warriors before the final battle with the Genji, foreshadowing their eventual fate, given an imminent defeat:

Fight with every breath

and every fibre

[…] for life without honour is not life!

These words parallel the principle behind the engraving on Butterfly’s dagger:

Con onor muore chi non può serbar vita con onore.

The dramatic irony of Tomomori’s resolution to retain his honour in desperate times reminds one of Butterfly’s Act 2 aria “Un bel dì”, where she blindly expects Pinkerton’s return despite the audience realising otherwise. Here, this mentality also separates the Heike’s persona from the Genji. As an adaptation of the historical Heike Monogatari, Sucharitkul’s libretto blurs the lines between protagonist and antagonist when representing the Heike and Genji, in contrast to the ‘cartoon’ antagonist Pinkerton.[21] Instead, he opted for a rounded, more ambiguous character development in keeping with the Heike’s narrative style. For example, the violent Genji generals are also shown to have humanity and an ambivalence towards war.[22] Despite that, they would advance against the Heike with great ferocity, as seen in Yoshitsune’s war cry:

Let us be pitiless

let us fall on the enemy

like a tempest

like a raging fire!

Tomomori and Yoshitsune’s war cries then exemplify the general mindset of their respective factions: the pursued Heike embraced a penchant for death and preservation of honour, while the Genji strived for relentless vindictiveness.

2.2 Social delineation in the libretto

Characters in both operas can be examined in light of their different social parameters, such as the divide between the Japanese and the Americans in Butterfly. Although there is no comparable divide in Dan-no-Ura, the characters differ in terms of their relative rank within the nobility, as reflected in their mutual interactions. Both operas show this type of social differentiation to some degree. It is important to understand, however, that despite a role in initiating plot conflict, they do not directly underpin the drama. Greenwald, for instance, believes Puccini’s toning down of the East-West conflict spotlights Butterfly’s trajectory that becomes the source of the drama. By accepting the existence of social differences, a comparison with Dan-no-Ura can be used to expose the exaggerations made by commentators who attempt to derive racial meaning from the libretto.

Groos interestingly noted that the text of Butterfly’s arioso “Io seguo il mio” is constructed with a peculiarly uneven rhyme and meter, which he opined as being the librettists’ depiction of Butterfly’s unsuccessful attempt to adopt Western culture,[23] perhaps analogously to how the original Long and Belasco sources intended this to illustrate Butterfly’s failure to “match” the superior Western culture through her language.

For instance, in Long’s version, her speech is marked with a conspicuous pidgin when in conversation with Americans, but with normal English with Suzuki and other Japanese characters (which is taken to represent perfect Japanese). In Puccini’s version, however, all her lines are converted to standard Italian throughout. Note, for example, the equivalent lines:

Chapter 10, Long: “Yaes; he go'n' come when the robins nest again.”

Act 2, Puccini: “Mio marito m'ha promesso di ritornar nella stagion beata che il pettirosso rifà la nidiata.”

Groos interprets the imperfect rhyme and meter in this arioso as being an alternative outlet to portray her lesser status as a Japanese with respect to the Americans. However, in light of Puccini’s efforts to tone down the East-West conflict and racist undertones in his sources, one can further conclude that the librettists’ did not intend to emphasise any racial differences. Not only does every character now speak the same language register, but this also implies that there is an “ideal” aria form in Puccini against which “Ieri son salita” is judged. As Bernardoni suggested, Puccini did not intend to use lyric verses and closed-form rhymes.[24] Take, for example, Pinkerton’s aria “Dovunque al mondo”, which contains equally uneven meter:

Vinto si tuffa, la sorte racciuffa.

Il suo talento

fa in ogni dove.

Così mi sposo all’uso giapponese

per novecento

novantanove anni.”

Since this is seen in both Butterfly and Pinkerton, who have no agenda on cultural emulation, text construction cannot justify Groos’s proposition.

In Dan-no-Ura, the notion of racial differences amongst characters is not present, nor does it concern the subject matter. However, the portrayal of class differences in the libretto is arguably much more apparent than the analogous racial differences in Puccini, due to the intricacy of the Heian-period nobility system. The interaction between characters, which are all of slightly different social ranks, is marked with noticeable difference in speech styles. This is apparent in the scene with Antoku and Amaterasu in Part 11, where she explains his imminent death in a grand, indirect language:

[...] Child, you are the dragon king reborn

You have come to the world

to reclaim your sword.

When speaking to the Sun Goddess, the Emperor is placed in an inferior status compared to her. Antoku also starts speaking in direct, short clauses, displaying his relative status, and in turn his child-like quality:

[…] and everywhere I go

There is music,

And every night

My grandmother sings to me

A pleasing lullaby.

Antoku’s mannerism here is markedly different than in the beginning of Part 3, when he speaks intelligently and displays dignified displeasure at Lady Dainagon-no-suke, his nurse, who is deceiving him from discovering Atsumori’s death:

You say so, you all say so.

But my heart knows

Who is telling the truth.

Antoku’s changes in speech register as reflected in relative verse length, therefore, serve a similar function to Butterfly’s alternation between normal and pidgin English in Long’s version. It is important to note that, as the dialogues including Amaterasu’s scene and all of Antoku’s lines are not found in the source, the presence of this characterisation shows Sucharitkul’s awareness of the intricate interactions between the various ranks of Heian nobles.[25]

2.3 The problem with Orientalisation

As both operas portray the Japanese culture in a non-Japanese context, it becomes a question to what extent this entails cultural appropriation or Orientalism, especially with Butterfly where the Japanese and their customs are contrasted against those of the Western characters. Most commentators suggest that Butterfly embodies the prevalent contemporary colonial attitude of a shallow, masculine West dominating an intriguing, effeminate East. McClary noted, for instance, that Pinkerton’s allusion in the libretto to Butterfly as a delicate insect to be caught and pinned down, and her defloration at the end of Act 1, is unique to Puccini’s version,[26] signifying Japan’s (and women’s) victimisation. Musically, his hedonistic, domineering behaviour is exemplified by a clearly defined entrance aria-space (“Dovunque al mondo”/”Amore o grillo”) overshadowing and displacing Butterfly’s identity,[27] as shown by her lack of a well-defined entrance aria.

These ideas are based on a questionable interpretation that assumes prejudicial intent. While Puccini depersonalises Butterfly’s character by not clearly defining her entrance, attributing this structural difference to racism is a weak critique. This strategy, whereby only the male protagonist is given an entrance aria, is not unique to Butterfly, but is also seen in Puccini’s other operas including Tosca: Cavaradossi is given “Recondita armonia” when Tosca enters in the middle of the subsequent scene, but it is not claimed that this lack of an entrance aria is somehow related to the oppression of Tosca’s character. Furthermore, Groos’ image of Butterfly’s blending into nature is consistent with the sociocultural value (wa) that emphasises on placing oneself in harmony with the natural surroundings.[28] Therefore, to immediately assign a racial connotation to this aspect of Butterfly here in favour of the presupposed Orientalist image would neglect Puccini’s aesthetically realistic portrayal of Japanese values. It can be seen instead as a “recipe” for Puccini’s dramaturgy that happens to tie in with Japanese aesthetic ideas in Butterfly, rather than signifying the protagonist’s oppression.

The question that follows is the degree of effeminacy in Japanese culture, and the extent to which it affected Western perception. As inferred from Tanizaki,[29] some Japanese people indeed consider themselves as being more nuanced and subtle than their Western counterparts due to their acknowledged different religious and aesthetic values. In Dan-no-Ura, for example, we see strong male characters being melancholic and appreciating beauty, as seen in Yoshitsune’s soliloquy lamenting Kumagae’s killing of Atsumori:

You understand me well,

Lord Kumagae,

who wept as you slew

your beautiful enemy.

This cannot be said of Pinkerton, who is portrayed as a “cartoon” antagonist whose one-dimensional, domineering views are not shared by the audience. This Japanese trait, as replicated from the original source, happened to coincide with the general fin-de-siècle attitude towards non-Western cultures as being intriguing and feminine. It is therefore more appropriate to regard the portrayal of the Japanese in Butterfly not solely as an act of overt cultural Orientalisation, but rather as a culturally grounded observation, incidental as it may be.

Amongst contemporary Milanese audience, there was still an implicit expectation of stereotypical Oriental qualities in Japanese culture, such as sexism and female oppression.[30] Dan-no-Ura, being outside of this bias, shows an almost complete subversion of these values. The female characters hold matriarchal authority and moral bearings to the same extent, if not even more than the male. This is exemplified by Nii Dono who, amidst the Heike’s impending destruction, shows a superior, unimpeded sense of duty to abide by her code of honour in light of Tomomori’s bickering:

Tomomori: Mother,

we are betrayed.

In a few heartbeats,

the Taira [i.e. Heike] will be no more.Nii Dono: Look at you and your men,

waiting […] like dogs.

[…] Are you men?

I am but a woman,

yet I know where my duty lies.

As this is lifted verbatim from the Heike Monogatari, it has many implications; especially given the composer’s denial of its subversiveness[31] (unlike David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly, which intentionally reversed the East’s victimisation in his reinterpretation of Madama Butterfly).[32] For example, it implies that the perception of gender roles inside Japan is different to outside views, whereby female oppression may not actually be present, at least during the time period the literature depicted.

Butterfly’s will to abide by her morals can then be compared with Nii Dono’s heroism. Their suicides are intended to avoid dishonour at the hands of men, viz. Pinkerton or the Genji. Like the Heike, Mimì or Manon Lescaut, Puccini aimed to portray Butterfly’s death with a tragic exaltation to draw a strong, compassionate audience reaction: a feature not found in earlier sources depicting Butterfly’s character simply as a pathetic Japanese caricature stemming from a deep-rooted cultural misunderstanding. Instead, she is humanised and pitied through her flaws (such as her inability to grasp reality). The same cannot be said for, say, Bizet’s Carmen, who has been described as “the embodiment of the vulgarity and immorality of Orientalism”. Here instead, her undesirable qualities (from the contemporary Western perspective) justified her equally shocking death, which is presumably intended to be viewed less sympathetically than that of Butterfly. Therefore, it can be postulated that, despite some contemporary influences on Puccini, much of the racial or gender issues previously attributed to Butterfly are collateral to its Japanese setting. Instead, it forms part of a running theme also present in many of Puccini’s other heroines – from Manon Lescaut,to (Liù) – that exalt their plight. The whole accusation that Butterfly exemplifies Orientalism can then be seen as a modern projection of Western regret at its own colonial past, revolving only within the Western psyche. Thus, it is understandable that Parker’s de-colonialist statement that Butterfly must not be performed due to its racist portrayal of Japan does not seem to be shared even by the Japanese themselves.[33]

3. Influence of Japanese Music in the Operas

Introduction

Puccini’s and Sucharitkul’s fundamental musical styles are ultimately derived from late-nineteenth-century common practice, with Italian and Wagnerian influences respectively. Both sought to employ authentic musical idiom of the locales in their works[34]. Although both scores indiscriminately use some exotic-sounding instruments to create an unfamiliar atmosphere[35], the musical styles show direct Japanese influence. Traditional musical idioms are employed in conjunction with their fundamental styles, but for different reasons. Puccini’s exoticism in Butterfly panders to the curiosity for foreign cultures in the 1904 Milanese, who had minimal contact with Japanese music, and therefore perceived the Japanese element as foreign, as evident in prevailing opinions around that time.[36]

On the other hand, Sucharitkul’s 2014 Bangkok audience comprised mainly of local members and Japanese expatriates and who would arguably be familiar with Japanese musical tropes to some extent. Therefore, as a “neo-Asian, neo-romantic”[37], Sucharitkul can be seen operating with a postmodernist domain, freely combining earlier Western styles with traditional Japanese idioms to feed into the audience expectation for an opera set in Japan, as evident in a review, which comments on the “Japanese touches … so characteristic of traditional Japanese drama.”[38]

Early commentators of Butterfly noted Puccini’s use of traditional Japanese melodies to merely invoke an exotic ambience; then Groos noted Puccini’s use of these idioms to portray characters and situations in detail. The grounds of exoticism cannot be applied, especially in the twenty-first century, to Sucharitkul, who had no intention of using the Japanese idiom to invoke the unfamiliar, given the audience’s shared familiarity with Japanese culture. Instead, he considers himself an “occidentalist” in this opera, whereby the Japanese idiom forms the basis of his thoughts, and onto which he then applies his common-practice style.[39] This would have an effect on his general style in the score (see below).

In this chapter, I aim first to show that although Puccini had more limited resources than Sucharitkul, both composers effectively fulfilled audience expectations of Japanese music, and that Butterfly’s musical idiom shows a greater extent of Japanese influence than previously suggested especially when examined in comparison with Dan-no-Ura. Then, I look at the ways Japanese idiom influences motivic development: by trying to apply new ways of examining motivic connections within both operas, I aim to prove that there is a deeper semantic representation in Butterfly’s motifs than previously realised. Lastly, I consider how different idioms, composer-fundamental or Japanese, are used to characterise groups of people, arguing that both works achieved similar effectiveness through analogous strategies.

3.1 Sources and utilisation of Japanese music

The fact that Sucharitkul had more access to Japanese music source materials than Puccini results from increased global knowledge of Japan over the last century. Japanese music only became known in the West after the reopening of trade in 1854, following a long isolationist period. Even then, it was not until the 1870s that traditional Japanese melodies were transcribed into Western-notated songbooks sold in Europe as curiosity items. Some of Puccini’s uninformed use of melodies in Butterfly would be understandable, given the scarcity of authentic sources available to him or other composers of Japan-based operas around this time, had they sought for them.

On the other hand, musical resource did not impede Sucharitkul who, having lived and studied in Tokyo for a period of time, was extensively exposed to traditional Japanese music[40] and therefore able to effectively utilise Japanese idioms. Thus, unlike Puccini, rather than borrowing traditional melodies, he extracted the tropes associated with different genres of Japanese music, with particular implications that will be discussed subsequently.

Whether Puccini and Sucharitkul utilised Japanese music true to its origin to portray the Japan in their works is a difficult question that needs to take into account whether it was intended or even necessary. It is true that Butterfly could be considered the most “musically Japanese” opera in the Western repertoire up to the point of its conception - with La princesse jaune (1872), The Mikado (1885) and Iris (1898) as predecessors - through the unusual length to which Puccini went to obtain his sources for authentic melodies compared to other composers. His intention to “represent the true Japan, not like [Mascagni’s] Iris” can be seen not only as a slight against his competitor, but also an aversion to merely portray exotic music using superficial instrumentation as per Mascagni[41] (Fig. 5), or exotic-sounding pentatonic melody per Saint-Saëns’ (which may even be recognised today as more Chinese-sounding than Japanese) (Fig. 6).

Groos discussed the original context of the various identified melodies in Puccini’s score and in what way he fulfilled this “intention”. However, his argument needs new evaluation in light of the surfacing new evidence on a hitherto unidentified melody. The “Young Butterfly” motif[42] had been identified by Groos as coming from a “1901 Bologna sketch”. An old Chinese music box rediscovered in 2012, believed to have been owned by Puccini, contains not only the “Mo Li Hua” melody that he later used in Turandot, but also what is purportedly the original tune of the “Young Butterfly” motif – “Shiba Mo”[43] (Fig. 7). The musical resemblance is much stronger here than in “Bologna sketch”, which only bears a passing resemblance in the contour of two bars, strongly suggesting that he had indeed used the music box as the source.[44] As “Shiba Mo” is a Chinese melody (which Puccini would have realised), that he did not distinguish it from Japanese music unfortunately does little to exonerate him from the same Orientalising attitude that caused him to lump the “music of the yellow race” together, just as Saint-Saëns did with the Chinese-sounding music in La princesse jaune.[45]

Fig. 5 - Act 3 opening, Iris.

Fig. 6 - Overture, La princesse jaune.

Fig. 7 - Aural transcription of “Shiba Mo” from Chinese music box. (x) denotes Puccini’s own modification into Butterfly.

Unlike Butterfly, Sucharitkul’s score is not subject to the “pan-Far East” issue on account of his familiarity with Japanese music. It does, however, present stylistic incongruities as he juxtaposes many disparate genres of Japanese music. This phenomenon is most apparent in Part 1 Chorus Prelude (Fig. 8). The type of music most appropriately representing the Heian aristocrats in Dan-no-Ura is the imperial court music gagaku, which is appropriately invoked here: the various percussion strikes represent the characteristic metal gong shōko and drum tsuri-daiko while the harp imitates the zither koto on the pentatonic yō scale. However, the piccolo, although appropriately imitating the flute ryūteki’s characteristic pitch bending, it employs the in scale not found in gagaku, and resembles only the instrumental music from a much later Edo/Meiji period during which most of the melodies in Butterfly originate. Despite being anachronistic here, this displays Sucharitkul’s informed artistic license as the piccolo’s melodic structure aptly captures the descending major 2nd→major 3rd interval, forming overall tritone (x) that is so characteristic of in scale and has become a trope synonymous with Japanese music, perhaps to pander to audience expectation of the Japanese idiom.

Fig. 8 - Part 1, Dan-no-Ura. (x) denotes intervallic trope.

Puccini himself was also likely to be aware of this distinctive sonority[46]: he weaved it into the melodic lines in a very similar, descending sequential fashion to Dan-no-Ura in “Tu, tu piccolo iddio”, as well as implying it with a heavy use of minor sixth chords (Fig. 9), showing a more integrated idiom in the score than simply having the melodies grafted onto it.

Fig. 9 - “Tu, tu piccolo iddio”, Act 3, Madama Butterfly. (x) denotes intervallic trope. Note the similarity between the descending tritone here and in Dan-no-Ura Fig. 8.

There is no evidence, however, that Puccini was aware of the meaning of most of the melodies that he quoted, save the national anthem “Kimigayo”[47], which he used in the Imperial Commissioner scene. As a result, for example, we see “Takai-yama”, a work song, appropriated as Suzuki’s prayer in Act 2, with no relation to its original tone or meaning. This creates a number of problems in Puccini’s music, at least to the discerning listener. Firstly, those who are aware of the original songs’ context might be unduly drawn to their decontextualized appropriation in the score, causing detachment from the drama onstage.[48] Secondly, Puccini’s originality needs to be called in question due to the extent to which these melodies are employed. For instance, the melodic structure of Butterfly’s Act 2 aria “Che tua madre” is based entirely upon three melodies “Jizuki-uta”,” Suiryō-bushi” and “Kappore-hōnen”[49], arguably making this aria one of Puccini’s least original. This fact would have been lost on his premiere Milanese audience, due to an equally limited exposure to Japanese music, thereby showing that Puccini’s use of Japanese sources is, like Sucharitkul, kept the extent of their knowledge in mind.

In contrast, by avoiding the use of existing melodic materials, Sucharitkul could not only able to flexibly and subtly incorporate the Japanese idiom into the score in a more integrated manner, but also averted the aforementioned side effects, especially towards an audience that likely would be somewhat acquainted with Japanese music. This is evident in a review of Dan-no-Ura that noted the opera as not being a “pastiche of Japanese music”,[50] justifying Sucharitkul’s strategy here.

Nevertheless, Puccini’s own Japanese material may have influenced his overall harmonic language more than some critics suggest. For instance, Budden[51] and Carner[52] propose that Debussy heavily influenced his use of whole-tone scales. However, neither of them seems to note the similarity of the whole-tone construction between the ending phrase of “Jizuki-uta” as found in Pinkerton’s cry “Butterfly!” near the end, and the Bonze’s motif (I:102) or Goro’s scene (II:27 bar 9), for example (Fig. 10). While there is possibly no semantic connection between any of them, the similarity in timbre shows that the influence of whole-tone construction that imparts Butterfly’s score may have equally resulted from a traditional scale as seen in “Jizuki-uta”. Hypothetically, another way to see this is that the use of whole-tone scale in both Puccini and Debussy (who himself had an interest in Oriental music) could ultimately derive from Japanese music similar to this song here.

Fig. 10 - Comparison between whole-tone motif from Japanese source and other similar ones, Madama Butterfly.

Sucharitkul attaches symbolic meaning to Japanese musical idioms more intricately than Puccini as he considered the historical association of his source materials, and not their musical face value. This is demonstrated in Part 11 whereby he alludes to Amaterasu’s divinity with the sound of gagaku mouth organ, the shō. In ancient gagaku theory, the high-pitched dissonant clusters of the shō represent light from the heavens[53] (from which Amaterasu is descended). It is portrayed with long, closed-voicing violin chords, creating sonority starkly different from what the audience would normally associate with Japanese music. The expressive gagaku sonority seems to further signify the harrowing moment in Part 10 when Shigeyoshi is discovered to betray the Heike, seen here in the long string cluster of fourths resembling the “Bō” chord[54] (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11 - Part 10, Dan-no-Ura.

It is hard to imagine that many in the audience would recognise these symbolisms owing to a limited public exposure to gagaku as a genre, which is almost exclusively used in connection with the Imperial family. Commoners of the Meiji era, in Butterfly, for instance, would perhaps not recognise it, but would recognise the popular melodies used in Puccini’s score. Another symbolism can be drawn here that the melodies in Butterfly aptly represents the common people portrayed in it, while gagaku represents the Heian nobles in Dan-no-Ura. Sucharitkul’s arcane gagaku allusion, therefore, not only demonstrates a well-informed addition of details below the surface, but also helps exemplify the difference in music found between the two social classes in Japan across 700 years.

3.2 Motivic development

The difference in source materials that both composers used directly influenced their different strategies in motivic development. As Puccini derived most Japanese elements in Butterfly from traditional melodies, he had significantly less flexibility in fragmenting them and attaching dramatic connotations to create a leitmotif, while that is not the case for Sucharitkul. However, that is not to understate the semantic significance of such motifs as the “pseudo-ume-no-haru”, as discussed in 1.2. It can then be seen that this is the most Wagnerian motif in the opera because of its varied dramatic foreshadowing activities.

Fig. 12 - (x) denotes similarity between “Shiba Mo” and “pseudo-ume-no-haru” motif.

To date, however, this motif has not been convincingly identified in any of Puccini’s sources, and it is not unreasonable to surmise that Puccini devised it himself. If true, this may help prove that an original motif is inherently better suited to leitmotivic activity, as Dan-no-Ura aptly demonstrates (see below). In fact, “Pseudo-ume-no-haru”’s motivic associations may be more wide-ranging than previously thought, as none of Puccini’s commentators seem to recognise the similarity of this motif with the “Shiba Mo” melody[55] (Fig. 12). Although hitherto unsubstantiated, it is conceivable that “pseudo-ume-no-haru” had been a partial motivic derivation of “Shiba Mo”. If so, this would greatly lessen criticisms of the superficiality of Puccini’s motivic approach.

While initially it may be hard to observe semantic connections between the two, we can posit that they are somehow related and complementary. “Shiba Mo” marks important points in Butterfly’s life-cycle: declaring her individuality at her entrance[56] (I:41) and her defloration (I:136). At the same time, “pseudo-ume-no-haru” represents the next stage of the life-cycle that is her death. The two motifs, therefore, represent the two sides of Butterfly’s life. To the listener, appreciating this connection would allow an appreciation of deeper meaning to Puccini’s compositional thoughts than previously credited by his detractors.

Sucharitkul’s score employed a very similar dual motivic relationship whereby two complementary Japanese-sounding motifs illustrate different aspects of the concept at hand. Part 7 of Dan-no-Ura in particular, when the Genji are first introduced, brings about two new motifs. The first, a short descending-ascending figure in yō scale, reflects the Genji’s warrior-like quality and heralds their entrances (Fig. 13). This motif alternates with a shorter, brisk ascending-descending motif in in scale, first introduced in the fashion of a fugal exposition (Fig. 14), its busy semiquaver-laden nature representing the Genji’s relentless pursuit of the Heike.[57] The two motifs’ opposite contour is obvious, with each highlighting the two main aspects of the Genji mentality. Moreover, the use of these fragmentary motifs, analogous to the “impermanence” and “shadow realm” motifs, enabled Sucharitkul to interweave them into complex orchestral parts, creating a score with a subtler but more dramatically meaningful use of Japanese materials in general compared to Puccini.

Fig. 13 - The “warrior” Genji motif, Part 7, Dan-no-Ura.

Fig. 14 - The “pursuit” Genji motif, Part 7, Dan-no-Ura.

3.3 Social delineation in the music

The social conflicts underpinning the drama in Dan-no-Ura stems from a political dispute between two factions, with class difference being collateral, while in Butterfly they ultimately stem from the East-West cultural differences. The Japanese element in the scores differentiates this to a certain degree. For instance, music helps define the cultural separation between America and Japan in Puccini’s opera even more than the preceding Long and Belasco’s versions, as this dimension is unavailable in their respective media. Bernardoni posits that in Puccini’s exotic operas, the conflict between exotic sounds and his diatonic, “Italian style” is contrasted by the fundamental differences in musical language.[58] Furthermore, relative cultural differences between Puccini’s “normative” realm and the different ethnicities/nationalities in his operas can be perceived on a spectrum of musical compatibility. In this case, the ‘Japanese’ music in Butterfly would be more distant on this spectrum due to its emphasis on tritones and minor sixth chords from the in scale, as well as other non-diatonic harmonies (Fig. 15). Meanwhile, the Americans are portrayed with familiar idioms such as diatonicism and arpeggio, as Budden suggests.[59]

Fig. 15 - Examples of harmony unique to passages derived from Japanese[60] sources, Madama Butterfly.

As the Japanese element pervades the orchestral and vocal textures (Fig. 16) of Dan-no-Ura’s score more thoroughly, it presents less stylistic conflict with Sucharitkul’s fundamental harmonic language. This is understandable, as the subject matter does not provide space for the musical portrayal of any ethnic conflict, which is the case with Puccini’s. However, we can instead use the parameter of class and faction to examine how Sucharitkul varies the use of the Japanese idiom.

Scott noted that, as a form of musical prejudice in exotic operas, lower class characters are more ethnically rooted, and so are portrayed with a more locale-appropriate music.[61] The Japanese element is especially concentrated in Part 7 with the introduction of lower ranking Genji, as discussed above. On the contrary, it is found in a lesser degree in the Heike protagonists’ music, especially high-ranking ones e.g. the Emperor and the Sun Goddess. The entirety of Part 11 duet, for example, has clear common-practice influences (Fig. 17), reflecting Sucharitkul’s fundamental style.

Therefore, a subtle form of characterisation by varying the “concentration” of Japanese music in the score is seen at play here, whereby more Western-sounding music represents the Heike, and a more Japanese idiom the Genji. Alternatively, a more Western idiom is associated with the higher-class characters - the immediate imperial family or the gods - but not to the same extent with the minor warrior characters. Interestingly, therefore, Sucharitkul’s use of Japanese music creates a sense of “otherness” to the characters with whom the audience are less likely to identify, which would be opposite to Puccini’s situation whereby the music of Butterfly and other Japanese protagonists instead utilises the Japanese idiom to a greater extent.

Fig. 16 - Examples of Japanese idiom in vocal and orchestral textures[62], Dan-no-Ura.

On that point, Groos noted that Japanese melodies in Butterfly are most concentrated in Act 1 when Goro introduces Butterfly and her family, or when “indigenous activities” are displayed, e.g. when Butterfly introducing her possessions. The original 1904 Milan version shows that many more of these Japanese-related scenes had been cut (the nephew’s antics, Yakuside’s drunkenness etc.), and with it are discarded many Japanese musical passages. Fairtile’s discussion on this topic only focuses on the cut’s effect on reshaping Butterfly’s character to become “less Japanese” by 1906, but did not note the resulting loss of Japanese music along with it. Therefore, the Japanese characters themselves in the 1906 Paris version, which since became standard, are seen to become less musically delineated overall.

Fig. 17 - Part 11 shows clear influence of the Romantic idiom, Dan-no-Ura.

Conclusion

This study hopes to show that, by comparing the different portrayal of Japanese culture with Dan-no-Ura, Butterfly depicts it more faithfully than previously said. Moreover, although we cannot deny a general Orientalising attitude during Puccini’s time, Madama Butterfly is not an inherently sexist or racist opera. There are also deeper meanings in the structure, motivic development and characterisation in both operas that can be derived when examined alongside each other. Nonetheless, Puccini’s depiction of Japan is not nearly as accurate as that of Sucharitkul who lived in Japan, studied Japanese culture, and used Japanese literature directly as a basis of his opera. Dan-no-Ura displays a deep understanding of religion, the Heian-period culture and genres of Japanese music. It can, therefore, be used as a standard for authentic depiction in opera. However, Puccini’s shortcomings are understandable given the relative lack of contact with contemporary Japan. Nevertheless, his efforts produced a depiction that was more culturally grounded than previous Japan-based operas.

By comparing the two, we see an increase in global awareness in which, over time, opera composers become more knowledgeable in the culture of the locales in which their works are set, which in turn produces more faithful depictions. As one of Thailand’s preeminent opera composers, Sucharitkul and his music deserves further study. At the same time, much of the critical literature that retrospectively value-judged Puccini must be re-evaluated if one accepts the arguments made here.

Appendix

1.1 Traditional Japanese music references

The Shō, or mouth organ, is a harmonic instrument in the gagaku orchestra made of seventeen pipes and fifteen reeds, whose function is to play one of the ten systematised long cluster chords, or the aitake (Fig. 17). The traditional way of shō playing involves gradually accruing the cluster notes from the bottom, creating an increasingly dissonant sound.

Fig. 17 - The shō’s aitake chords, as transcribed by Garfias (1975).

The two most prevalent pentatonic scales found in traditional Japanese music are the in and yō scales (Fig. 18). The in is mostly found in traditional songs and instrumental music for the koto and shamisen. The yō, on the other hand, is found in gagaku and shōmyō chanting.

Fig. 18 - The in and yō scales.

Note the difference to the intervallic structure in the pentatonic scale normally associated with Chinese music, the gong scale (Fig. 19), as seen in La princesse jaune overture, “Shiba Mo”, “Mo Li Hua” and “Signore, ascolta!” in Turandot, I:62 in Madama Butterfly, for example.

Fig. 19 - The Chinese gong scale.

1.2 The Heike Monogatari

The Heike Monogatari (c. 1240) is an epic war tale from the Kamakura period (1185-1333) recounting an actual historical struggle between the Taira/Heike (a direct Imperial line) and Minamoto/Genji families in a civil war that marks the end of the Heian period, known as an age of flourishing artistic and literary development. In the story, Yoshitsune of the Genji is portrayed as a samurai hero, whereas in the opera his antagonistic qualities are highlighted against the main Heike characters. The main theme in the epic lies in the Heike’s downfall, which culminates in the battle of Dan-no-Ura where they drowned in a mass suicide in the face of capture, after suffering a series of defeats. In the epic, their downfall is equated to the Buddhist message of impermanence, as shown in the famous first lines which Sucharitkul set for the Chorus Prelude/Postlude:

The sound of the Gion Shōja bells echoes the impermanence of all things; the color of the sāla flowers reveals the truth that the prosperous must decline. The proud do not endure, they are like a dream on a spring night; the mighty fall at last, they are as dust before the wind. - McCullough (1988)

1.3 Dan-no-Ura

Sucharitkul inherited the main message of impermanence from the Heike Monotagari, which plays out both in the libretto, characterisation and the music. He further speaks of adapting the epic into the opera in a programme note for its premiere on 11-12 August 2014:

Like the Iliad, the Tale of the Heike is a "national epic" set in a remote time in which the heroes and heroines are larger than life and speak of Big Concepts like honour, loyalty, devotion, and sacrifice. But also like the Iliad, and unlike many other "national epics", the Tale of the Heike shows us human beings that are completely recognizable in the contemporary world, and in my opera I have tried to draw all of them as complex individuals that people today will recognize: the strong matriarch (Nii Dono) who sees with crystal clarity what her sons (Munemori, Tomomori) are too blinded to see, the bickering Heike generals with their individual agendas, the powerful Genji warriors (Yoshitsune, Kumagae) who know they are trapped in an escalating cycle of destruction, the boy-Emperor (Antoku) who is so close to death that he can already speak to the dead (Atsumori) and to the Gods (Amaterasu) themselves. In fact, the idea of warring factions who shouldn't be at war has a powerful resonance with where we are today in this country, and the important lesson the epic teaches, which is that "the proud fall in the end ... like a dream in a spring night they are like dust in the wind" is one that people today should take to heart.”

The synopsis, full score, libretto and character list in Dan-no-Ura can be found under the following link:

www.goo.gl/u4mzw9 (A Google Drive directory)

Note that the “Scenes” in the synopsis and “Parts” in the score do not completely match. This is explained in the synopsis.

Somtow Sucharitkul’s autobiography and list of works can be found under the following link:

1.4 The concept of beauty in Japan

The beauty standard in the Heian period amongst the noble classes emphasises the fairness of the skin that would divert the attention from other facial features: the eyes, the eyebrows and the mouth, in order to make the face more visible when viewed in dimly-candlelit rooms of the time. As a result, a practice developed whereby the eyebrows are shaved off and demurely painted over. At the same time, the entire oral cavity is painted black in order to hide all the inner features in the prevalent practice of ohaguro. There is no evidence of this practice, either in Loti’s account or in any versions of Butterfly, that describes this practice with her character, as to be expected with geishas during the period in which the story is set. In fact, Butterfly is set in an interesting time period when this custom was being banned for being “too native” as part of the Meiji government’s westernisation efforts. However, these practices were faithfully replicated by the designer Nattawan Santiphab in the female characters of Dan-no-Ura’s premiere, except for the ohaguro. According to the composer, the original plan of its inclusion was discouraged as it was feared that the ohaguro would prove distracting to the Bangkok audience of 2014. Similar aesthetic decisions were made in the 2005 NHK Series Yoshitsune, which depicts the same story of the Dan-no-Ura battle, whereby the female characters employ remarkably similar appearance devoid of ohaguro.

Fig. 20 – Faithful reproduction of Heian-period aristocratic fashion in Dan-no-Ura. Shown here is Lady Dainagon-no-suke played by Nadlada Thamtanakom.

1.5 Music for Americans in Puccini

As Budden noted, the music for Americans (“Western themes”) in Madama Butterfly is often marked with the use of arpeggio. Similar ideas can be seen in La fanciulla del West as well (Fig. 21).

Fig. 21 - compare Sharpless’ passage with Jake Wallace’s melody.

1.6 Japanese Melodies in Madama Butterfly

A list of Japanese melodic sources used in Madama Butterfly and their placement in the score can be found under the following link:

http://daisyfield.com/music/htm/-colls/Puccini.htm

Bibliography

Adami, Giuseppe, ed., Letters of Giacomo Puccini: Mainly Connected with the Composition and Production of His Operas, 1931, Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott.

Belasco, David, Madame Butterfly: A Tragedy of Japan, 1928, http://www.columbia.edu/itc/music/NYCO/butterfly/images/belasco_sm.pdf. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Budden, Julian, Puccini: His Life and Works, 2006, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carner, Mosco, Madam Butterfly, 1979, London: Breslich & Foss.

Carner, Mosco, Major and Minor, 1980, London: Duckworth.

Cooke, Mervyn, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-century Opera (Cambridge Companions to Music), 2005, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dolan, Ronald E. and Worden, Robert L. ed., Japan: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1994.

Garfias, Robert, Music of a Thousand Autumns: The Tōgaku style of Japanese Court Music, 1975, London: University of California Press.

Gayuski, Stan, ‘Somtow delivers a samurai epic’, The Nation, 2014,

(http://www.nationmultimedia.com/life/Somtow-delivers-a-samurai-epic-30241371.html. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Groos, Arthur, ‘Return of the native: Japan in Madama Butterfly / Madama Butterfly in Japan’, Cambridge Opera Journal, 1(2), 1989, 167-194, http://www.jstor.org/stable/823590. [Accessed 26 April 2018].

Groos, Arthur, ‘Cio-Cio-San and Sadayakko Japanese Music-Theater in Madam Butterfly’, Monumenta Nipponica: Studies on Japanese Culture Past and Present, 1999, 54(1), 41-74, www.jstor.org/stable/2668273. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Greenwald, Helen M., ‘Picturing Cio-Cio-San: House, screen, and ceremony in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly’. Cambridge Opera Journal, 12(3), 2000, 237-259, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3250716. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Hara, Kunio, Puccini's Use of Japanese Melodies in Madama Butterfly, 2003, MA Thesis (University of Cincinnati).

Iggulden, Amy, ‘Opera expert says Puccini's Butterfly is 'racist'’, The Telegraph, 2007, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1542633/Opera-expert-says-Puccinis-Butterfly-is-racist.html. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Keown, Damian, ‘Shinbutsu Bunri’, A Dictionary of Buddhism, 2004, http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198605607.001.0001/acref-9780198605607-e-1649. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Kerman, Joseph, Opera as Drama, 1988, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Komada, Haruko, ‘Theory and Notation in Japan’ The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: East Asia: China, Japan, and Korea, 2002, New York: Routledge, 565-584.

Long, John L., “Madame Butterfly”, 1898, http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/long/cover.html. [accessed 26 April 2018].

McClary, Susan, Georges Bizet, Carmen, 1992, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCullough, Helen C., The Tale of Heike, 1988, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

New World Encyclopedia contributors, "Shinbutsu shugo," New World Encyclopedia, 2015, http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Shinbutsu_shugo&oldid=990674 [accessed April 26, 2018].

Parkes, Graham and Zalta, Edward N., ed., ‘Japanese Aesthetics’, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2017, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/japanese-aesthetics/.

[accessed 26 April 2018].

Puccini, Giacomo, Madame Butterfly: Full Score, 2000, Milan: Ricordi.

van Rij, Jan, Madame Butterfly: Japonisme, Puccini, and the Search for the Real Cho-Cho-San, 2001, Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press.

Scott, Derek, ‘Orientalism and Musical Style’, The Musical Quarterly, 82(2), 1998, 309-335, http://www.jstor.org/stable/742411. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Sheppard, W. Anthony, ‘Music Box as Muse to Puccini’s ‘Butterfly’’, 2012 The New York Times,

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/17/arts/music/puccini-opera-echoes-a-music-box-at-the-morris-museum.html. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Smits, Gregory, ‘Chapter 3: The Heian Period Aristocrats’, Topics in Japanese Cultural History, http://figal-sensei.org/hist157/Textbook/ch3.htm. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Sucharitkul, Somtow, Dan-no-Ura - complete full score, 2014, Bangkok: unpublished.

Tanizaki, Junichiro, In Praise of Shadows, 1977, http://pdf-objects.com/files/In-Praise-of-Shadows-Junichiro-Tanizaki.pdf. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Wilson, Alexandra, The Puccini Problem: Opera, Nationalism and Modernity; 2007, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wilson, Conrad, Giacomo Puccini, 2008, New York: Phaidon Press.

Wisenthal, Jonathan, ed., A Vision of the Orient: Texts, Intertexts, and Contexts of Madame Butterfly, 2006, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Webography

Morris Museum, ‘Puccini's Madama Butterfly & Morris Museum's 1877 Musical Box: "Shiba mo" (The Eighteen Touches)’, 2012, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LhatQ4hTF_A. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Potter, Tom, Japanese Songs in Puccini's Madama Butterfly, Daisyfield, 2006, http://daisyfield.com/music/htm/-colls/Puccini.htm. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Okamura, Takao, ‘The revised edition of Puccini's Madama Butterfly’. NPO Opera del Popolo, 2003, http://www.minna-no-opera.com/eng/opera/2004_btt_gui_e.htm. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Proudfoot, Michael, ‘Review of “Dan-no-Ura”, Thailand Cultural Centre, 11th and 12th August’, Somtow, 2014, http://www.somtow.com/new-page-2/. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Wooster, Martin M., Operacon Report, http://file770.com/?p=21462, File770. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Sonica, ‘Sho’, Sonica, http://sonica.jp/instruments/index.php/en/products/sho. [accessed 26 April 2018].

Notes

[1] New World Encyclopedia contributors, "Shinbutsu shugo," New World Encyclopedia, 2015.

[2] “Act 1, rehearsal number 105”. (Puccini’s libretto contains no breakdown, so it is better to go by the score’s rehearsal numbers.)

[3] Takao Okamura, ‘The revised edition of Puccini's Madama Butterfly’. NPO Opera del Popolo, 2003.

[4] Arthur Groos, ‘Return of the Native: Japan in Madama Butterfly / Madama Butterfly in Japan’, Cambridge Opera Journal, 1(2), 1989, 170.

[5] Antoku’s great-great-grandmother in the libretto.

[6] Damian Keown, ‘Shinbutsu Bunri’, A Dictionary of Buddhism, 2004.

[7] See 1.3.

[8] This is known in Japanese as “aware”. Graham Parkes and Edward N. Zalta, ed., ‘Japanese Aesthetics’, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2017.

[9] See Appendix.

[10] Helen H. Greenwald, ‘Picturing Cio-Cio-San: House, Screen, and Ceremony in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly’, Cambridge Opera Journal, 12(3), 2000, 237.

[11] Julian Budden, Puccini: His Life and Works, 2006, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 253.

[12] Jonathan Wisenthal, ed., A Vision of the Orient: Texts, Intertexts, and Contexts of Madame Butterfly, 2006, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 10.

[13] Parkes and Zalta, ed., 2017.

[14] Arthur Groos, ‘Cio-Cio-San and Sadayakko Japanese Music-Theater in Madam Butterfly’, Monumenta Nipponica: Studies on Japanese Culture Past and Present, 1999, 54(1), 53.

[15] Joseph Kerman, Opera as Drama, 1988, Berkeley: University of California Press, 14.

[16] See Appendix.

[17] Stan Gayuski, ‘Somtow delivers a samurai epic’, The Nation, 2014.

[18] Groos, 1989, 173.

[19] Greenwald, 237.

[20] See 1.2 and Appendix.

[21] Wisenthal, ed., 23.

[22] See 1.2.

[23] Musically, this can be seen further in the arioso’s Western harmonic language tinged with exotic-sounding raised scale-degree 5→6. See 3.2.

[24] Mervyn Cooke, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-century Opera (Cambridge Companions to Music), 2005, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 31.

[25] Gregory Smits, ‘Chapter 3: The Heian Period Aristocrats’, Topics in Japanese Cultural History.

[26] Wisenthal, ed., 22.

[27] Groos, 1999, 62.

[28] Ronald E. Dolan and Robert L. Worden, ed., “Values and Beliefs”, Japan: A Country Study. Washington: GPO, 1994.

[29] Junichiro Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, 1977, 5.

[30] Groos, 1999, 54.

[31] Sucharitkul said that he “did nothing to challenge the worldview of the original characters”. Personal communication with the composer.

[32] M. Butterfly. See Wisenthal, ed., 10.

[33] Amy Iggulden, ‘Opera expert says Puccini's Butterfly is 'racist'’, The Telegraph, 2007.

[34] e.g. the Roman matin bells in Tosca and an original pavane/galliard in Suriyothai.

[35] Sucharitkul appropriated the Thai hand cymbal ching in the score, while Puccini called for a nonexistent “tam-tam giapponese”.

[36] Groos, 1999, 42.

[37] Martin M. Wooster, Operacon Report, File770.

[38] See Appendix.

[39] Personal communication with the composer.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Mascagni only learned of Japanese music through Baron Kraus’ instrumental collection. See Ibid., 43. His score, however, did not capture Japanese idiom.

[42] Wisenthal, ed., 48.

[43] W. Anthony Sheppard, ‘Music Box as Muse to Puccini’s ‘Butterfly’’, 2012 The New York Times.

[44] The A major key and arpeggiated accompaniment also resembles Butterfly’s arioso, I:80, in which it is used.

[45] In addition, McClary noted that the “Un bel dì” melody is a japonaiserie. However, its pentatonic scale is clearly the Chinese type, not Japanese, which further substantiates Puccini’s confusion. See Wisenthal, ed., 24. See also Appendix for Chinese/Japanese scales comparison.

[46] Notably seen in “Sakura” and “Echigo-jishi”, etc. in his source.

[47] Which he learned directly from Madame Ōyama, wife of Japanese ambassador.

[48] The Japanese melodies indeed did not go unnoticed by the 1923 Tokyo premiere audience. Groos, 1989, 178.

[49] Kunio Hara, Puccini's Use of Japanese Melodies in Madama Butterfly, 2003, MA Thesis (University of Cincinnati), 81.

[50] Michael Proudfoot, ‘Review of “Dan-no-Ura”, Thailand Cultural Centre, 11th and 12th August’, Somtow, 2012.

[51] Budden, 271.

[52] Mosco Carner, Major and Minor, 1980, London: Duckworth, 139.

[53] Sonica, ‘Sho’, Sonica.

[54] Robert Garfias, Music of a Thousand Autumns: The Tōgaku style of Japanese Court Music, 1975, London: University of California Press. See Appendix.

[55] Puccini seems to strongly associate the F#-A-F#-A-B melodic figure and Japan. Budden, 265.

[56] Groos, 1999, 62.

[57] As tension onstage grows, this motif is placed on a stretto in its third appearance, displaying Sucharitkul’s awareness of the fugal technique and its drama-heightening function.

[58] Cooke, ed., 31.

[59] Budden, 250. Arpeggios seem to be a trait Puccini assigned to music for the Americans. See Appendix for comparison with La fanciulla del West.